by Matthew Kennedy

Only months ago, highly explosive crude oil began to flow through the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), or the Black Snake, as it was named by the Indigenous and allied activists at Standing Rock who organized massive opposition to its construction. The pipeline has since then leaked five times along its route. Proposals for dangerous new fossil fuel projects will continue to multiply, per the extremist deregulatory agenda of the Trump administration. But the fierce struggle for Lakota & Dakota territorial sovereignty (and rights for all Indigenous peoples, more broadly), together with the persistent legal confrontation of DAPL and the U.S. government, have left a formidable legacy for the coming years.

One of many testaments to this legacy is a “floating pipeline resistance camp” which has formed “in the swamps of Houma, Chitimacha, and Chata territory” in southern Louisiana to halt the expansion of a related Energy Transfer Partners scheme: the Bayou Bridge Pipeline (BBP). The BPP is the southernmost leg of DAPL. A new stretch of the BBP would carry fracked Bakken crude via Nederland, TX and Lake Charles, LA to terminals in St. James, LA. Anti-pipeline organizers, coming together in June of last year, have named their camp, L’eau Est La Vie, a cajun variation on the Water Protectors’ Lakota, mni wiconi, or “water is life.” An inaugural announcement from the Indigenous Environmental Network read:

“L’eau Est La Vie camp is opening in resistance to the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, another Energy Transfer Partners project. BBP is the tail end of the Dakota Access Pipeline that weaves from the Bakken to the fragile wetlands of Southern Louisiana. Once again Indigenous communities are being put in harm’s way and over 700 bodies of water will be threatened by one of the worst environmental offenders known to date. We stand with the Water Protectors here in southern Louisiana to protect these critical wetlands that serve as protection for the people of this region from floods and storms.”

The United Houma Nation, whose cajun French/Houma-French creole gave the camp its name, is a tribe dwelling across the bayous and canals of the Gulf Coast, and it is one of several communities who would have much to lose in the event of a spill. The tribe, along with hundreds of thousands of others, depends for drinking water on Bayou Lafourche, which the pipeline has been permitted to pass narrowly beneath. The Houma’s lifestyle has already been forever altered because of coastal erosion, due to poorly regulated industrial activity and to rising sea levels. Officially recognized by the state of Louisiana, the United Houma Nation is still, after decades of frustration, seeking federal recognition.

Many of the “critical wetlands” discussed by the IEN belong to the Atchafalaya Basin, one of the largest and most productive wetlands on Earth, and a source of drinking water for over a million people. The BBP’s right-of-way would cross and further damage the Basin’s ecosystems, which have already been disturbed by past oil and gas activities, and would make them vulnerable to spillage. Among the diverse forms of wildlife who find their habitat within the Basin, highly at risk is the region’s crawfish population, a precious resource for the local economy and a sacred animal to the Houma.

At its destination, the new segment of the BBP would increase the toxic burden in St. James Parish (widely known as “Cancer Alley”), whose predominantly Black and working-class community is already saddled with hazardous oil and gas facilities, by bearing a huge volume of volatile Bakken oil to refineries and export terminals there. The pipeline obviously poses risks and injustices on a variety of different fronts. Tribal members, generations-old crawfishermen, environmental justice advocates, landowners and other residents have thus rallied together to express their dissent. Already L’eau Est La Vie has brought about a rerouting of the pipeline, but their grave concerns persist, and they pledge continued action alongside others in the state to stop the pipeline.

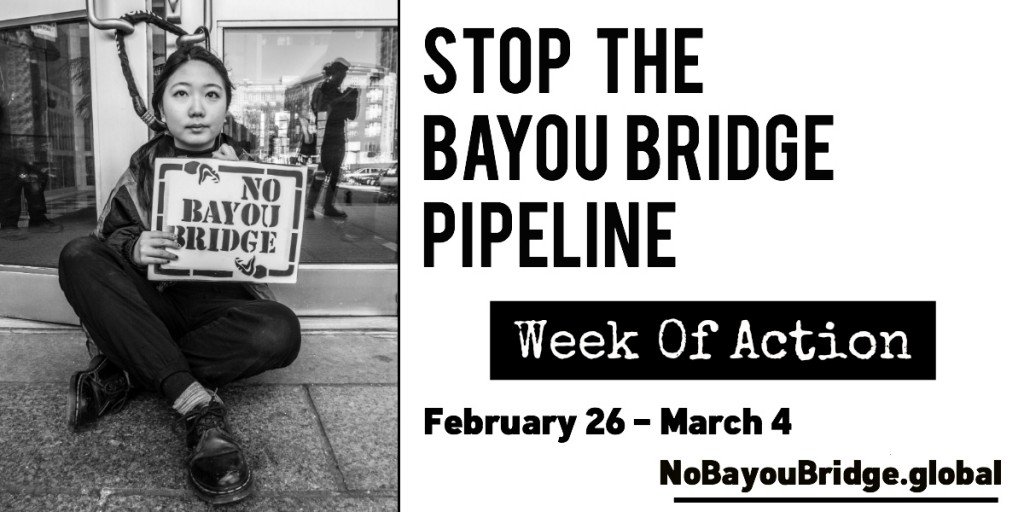

L’eau Est La Vie has invited committed activists, ready to support and respect Indigenous, Black, local, and femme organizers, to join the camp. They have also called for donations, in the form of money or supplies, including medicinal herbs. Their solidarity campaign has planned a Week of Action from February 26th to March 4th, pressing for demonstrations targeting BBP’s major funders as well as the Army Corps of Engineers, which permitted the project to be built. Energy Transfer Partners must be confronted throughout the Bakken pipeline system, wherever they attempt to transport fracked oil and endanger environmental health, local livelihoods, and Indigenous territory. Louisiana residents must not be made to endure further insult by reckless fossil fuel corporations.

Says Cherri Foytlin of BOLD Louisiana: “The corporation Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) has proven themselves to be untrustworthy in regards to their moral responsibility to preserve both human and ecological rights. Whereby they have obfuscated the truth, sabotaged democracy, destroyed our lands and water, and even hired mercenaries to injure our people, we have but one recourse, and that is to say ‘you shall not pass.’ No Bayou Bridge! We will stop ETP. They are not welcome here – not in our bayous, not in our wetlands, not in our Basin, not under our lands or through our waters. Period.”